Nail

2022-03-30 2022-03-30 15:00Nail

Nail

Introduction

Although nonoperative treatment for stable closed tibial fractures may give good results [12, 13], unstable closed and grade I and II open fractures of the tibial shaft are now treated with intramedullary nails, with or without locking [1–5, 8, 17]. Although interlocked nailing can achieve stable fixation and a high union rate [1, 2, 5], it is more difficult to apply and is time consuming. There is an increased risk of intraoperative complications [1, 2]. In contrast, the technique of unlocked nailing is simple. However, cast immobilisation is required due to its essentially poor control of rotation [4]. Because it is unclear which is the best method to treat a tibial shaft fracture, we were inspired to prospectively compare the clinical outcome of patients treated with unlocked and interlocked nailing

Patients and methods

Although nonoperative treatment for stable closed tibial fractures may give good results [12, 13], unstable closed and grade I and II open fractures of the tibial shaft are now treated with intramedullary nails, with or without locking [1–5, 8, 17]. Although interlocked nailing can achieve stable fixation and a high union rate [1, 2, 5], it is more difficult to apply and is time consuming. There is an increased risk of intraoperative complications [1, 2]. In contrast, the technique of unlocked nailing is simple. However, cast immobilisation is required due to its essentially poor control of rotation [4]. Because it is unclear which is the best method to treat a tibial shaft fracture, we were inspired to prospectively compare the clinical outcome of patients treated with unlocked and interlocked nailing.

Patients and methods

Between May 2002 and May 2005, 126 consecutive patients with tibial shaft fractures were operatively treated in our orthopaedic department. Inclusion criteria for this study were: (1) acute and unilateral fractures; (2) middle-third fractures or distal-third tibial fractures with at least 5 cm of distance from the fracture site to the ankle plafond; (3) intramedullary fixation with either an unlocked or an interlocked nail; (4) patients with the ability to walk without any assistance before injury. Exclusion criteria for this study were: (1) proximal-third fractures; (2) nonunion and pathological fractures; (3) severe open fractures (Gustilo grade III); (4) fractures involving the ankle joint such as pilon fractures; (5) requiring intensive care or requiring other departments for treatment. The 92 patients who met the inclusion criteria were randomly distributed to five senior surgeons according to their assigned shifts. These patients were treated either with an unlocked nail (ULN) or an interlocked nail (ILN) in turn. Ten patients could not be followed up regularly due to death (one case), co-morbid psychological disorders (two cases) or relocation (seven cases), and they were excluded. Eighty-two patients with an average age of 41.6 years were followed up for 12 months after discharge from the hospital and were included in this study. There were 17 open fractures including 13 Gustilo type I and four type II. An open fracture was treated by irrigation, thorough debridement and appropriate intravenous antibiotics. After fixing the fractures, the wound was left open or was approximated loosely to cover most of the exposed bone, according to the condition of soft tissue.

The 82 patients were divided into two groups, based on the method of treatment. The ULN group included 42 patients with an average age of 43.1 years. Thirty-five patients (83.3%) suffered from vehicular trauma. There were ten open fractures including eight type I and two type II. The ILN group included 40 patients with an average age of 40.0 years. Thirty-three patients (82.5%) suffered from vehicular trauma. There were seven open fractures including five type I and two type II (Table 1).

Table 1

Preoperative demographics and associated medical conditions in the two groups

| Unlocked | Interlocked | P | |

| Vehicular trauma (*N) | 35 | 33 | 1.0 |

| High-energy fall (*N) | 2 | 4 | 0.43 |

| Sports injury or minor trauma (*N) | 3 | 1 | 0.62 |

| Other injury (*N) | 2 | 2 | 1.0 |

| Middle-third fracture (*N) | 30 | 32 | 0.45 |

| Distal-third fracture (*N) | 12 | 8 | 0.45 |

| Open type I | 8 | 5 | 0.55 |

| Open type II | 2 | 2 | 1.0 |

| Gender (F/M) | 18/24 | 21/19 | 0.51 |

| Mean age (years) | 43.1 | 40.0 | 0.38 |

| Hypertension (*N) | 2 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Diabetes (*N) | 1 | 2 | 0.61 |

| Renal diseases (*N) | 1 | 0 | 1.0 |

| Respiratory (*N) | 1 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Heavy smoker (*N) | 3 | 3 | 1.0 |

In the ULN group, the operations were performed under spinal anaesthesia. The patients were placed in a supine position with the injured extremity in acute flexion at the knee joint. Closed reduction of the fracture was performed under an image intensifier. A standard medial parapatellar approach was used, and the starting point was opened by using an awl. A tibial Kuntscher nail (I.Q.L) between 8 and 12 mm in diameter was inserted through the patellar tendon without reaming. The nail was carefully hammered in. If the nail became stuck, it was removed and a smaller one was inserted. Fluoroscopy was used to verify the nail length and post-reduced fracture site. If marked fracture angulation was noted under fluoroscopy, gentle closed reduction was done before casting. An above-knee cast was used for 4 weeks. The patients then started progressive weight bearing in a below-knee cast with free movement of the knee for another 4 weeks. All patients were told to avoid work with heavy loads or aggressive exercise using the involved extremity during the following 3 months. In the ILN group, a standard medial parapatellar approach was applied, and the starting point was opened by using an awl. After placing the guide wire central to the distal subchondral plate, the intramedullary canal was reamed till appropriate fit of the reamer in the canal was achieved. During reaming, the alignment of the fractures was maintained and checked repeatedly with the image intensifier. After the canal was well-prepared, a Russel-Taylor tibial interlocking nail (Smith and Nephew Richards Inc., Memphis, TN) of the appropriate size was selected with a diameter of 1 mm narrower than that of the final reamer. After insertion of the nail into the distal tibia, at least one distal screw provided sufficient rigid stability. An above-knee splint was applied for 1 week. A short leg splint for soft tissue healing was given to all of the patients for another 2 weeks. Upon discharge from the hospital, the patients were allowed to toe-touch weight bear until the wound had healed. After 4 weeks, patients were permitted to increase their weight bearing

Plain films in the immediate postoperative period were reviewed for the adequacy of fracture reduction for all 82 patients. Varus-valgus alignment was determined by measuring the angle between the lines drawn perpendicular to and bisecting the tibial plateau and proximal medullary canal with a line bisecting the distal medullary canal and tibial plafond on anteroposterior radiographs. Anteroposterior alignment was determined by measuring the angle between a line parallel to the proximal fragment and a line parallel the distal fragment on lateral radiographs. We defined excellent reduction as <2 mm of fracture gap and approximately 5° of angulatory deformity in any plane (valgus/varus or anterior/ posterior). Good reduction was regarded as 2 to 5 mm of fracture gap and approximately 5° of angulatory deformity in any plane. Poor reduction was given for >5 mm of fracture gap or >5° of angulatory deformity in any plane. Adequate reduction included excellent and good reductions. Bony union was defined as evidence of bridging callus across the fracture sites or the obliteration of the fracture lines based on X-ray findings. Malunion was defined as fractured healing >5° of angulatory deformity in any plane, or internal rotation of 10° or more, external rotation of more than 15° or shortening of 2 cm or more. Nonunion was defined as no evidence of healing after 6 months.

Twelve months postoperatively, we evaluated the functional outcome using the functional score of Karlstrom and Olerud [9]. In this system, the clinical data are evaluated, including pain, impairment of walking, climbing stairs, or previous sports activity, work limitation, skin condition, deformity, muscle atrophy, length discrepancy, loss of knee movement, loss ankle movement and loss of pronation/supination. There are three grades (1, 2 and 3 points) in each item, and the maximum score is 36 points.

In both groups, the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for analysis of the gender versus type, associated medical condition, reduction rate, union rate, malunion rate, complication rate, rate of return to previous work and rate of return to the same athletic activities. A Student’s t-test was used for comparison of the age, operating time, wound size, hospital stay and functional score. Operating time was measured from the beginning of surgery to skin closure. The statistic software SPSS 10.0 was used to analyse the data: P values below 0.05 were considered significant

Results

Both groups were similar in the injury mechanism, fracture location, open fracture type, mean age, gender and associated medical condition (all P values were approximately 0.38) (Table 1). The operative time was significantly less in the ULN group when compared to the ILN group (P < 0.001). The wound size was also significantly smaller in the ULN group when compared to the ILN group (P < 0.001). There was no significant difference (P=0.28) in hospital stay between the ULN group (average: 5.9 days, range: 3-10 days) and the ILN group (average: 5.1 days, range: 3–9 days). In the ULN group, all but one fractures healed in 6 months (Fig. 1). The mean healing time was 16.2±4.6 weeks. In the ILN group, healing occurred in all but two cases (%) in 6 months with a mean of 18±3.3 weeks. The nonunion was treated by exchange nailing and autologous bone grafting. The union rate and healing time were not significantly different between the two groups (P=0.61, 0.33, respectively) (Table 2).

A 45-year-old female patient with right distal-third tibial fracture was treated with unlocked nailing. a Preoperative lateral view showed a displaced and spiral tibial fracture. b Radiograph at the immediate postoperative period showed excellent fracture reduction. c Radiograph at 16 weeks postoperatively showed fracture healing

Table 2

Operative data, hospital stay, union rate and healing time in the two groups

| *ULN (mean ± SD) | +ILN (mean ± SD) | P | |

| Wound size (cm) | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 8.1 ± 2.2 | <0.001 |

| OP time (min) | 24 ± 8 | 78 ± 24 | <0.001 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 5.9 ± 1.4 | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 0.28 |

| Union rate | 41/42 | 38/40 | 0.61 |

| Mean healing time (weeks) | 16.2 ± 4.6 | 18 ± 3.3 | 0.33 |

Evaluation of the immediately postoperative roentgenograms for adequacy of reduction revealed excellent results in 42.9% (18 cases) of the ULN group and 70% (28 cases) of the ILN group. Good reduction was achieved by 50% (21 cases) of the ULN group and 27.5% (11 cases) of the ILN group. Poor reduction was shown in 7.1% (three cases) of the ULN group and 2.5% (one case) of the ILN group. The adequate reduction rates between the ULN group (92.9%) and the ILN group (97.5%) showed no significant difference (P = 0.62).

With regard to malalignment, four individuals in the ULN group (9.5%) had malunion including two fractures with 6° and 10° anterior malalignment, one with 10° posterior angulation, and the remaining one had 7° valgus deformity. Clinically, there was no case of significant tibial shortening. In particular, three of the four malunions involved distal-third fractures and the remaining one occured in a middle-third fracture. In the ILN group B, there was one malunion (2.5%) with 8° posterior angulation. The malunion rates between the ULN group (9.5%) and the ILN group (2.5%) showed no significant difference (P = 0.36). However, in the ULN group, distal-third fractures showed a trend towards increased malunion rate when compared to middle-third fractures, although this was not significant (3/12 versus 1/30, P = 0.06).

The ULN group had four early complications (9.5%) that were related to nail migration. Two of them had early removal of the involved nails as fracture healing progressed. The remaining two required exchange to a larger nail. The ILN group had four early complications (10%) including a superficial infection, one deep infection, and two with broken locking screws. The superficial infection occurred in a closed fracture of a diabetic patient with poor control of blood sugar. She was diagnosed clinically at the first follow-up visit about 8 days after surgery. After 7 days treatment with oral antibiotics, the wound healed uneventfully. The deep infection occurred in an open type II fracture. Although an organism-specific antibiotic was given parentally in this patient, persistent drainage from a wound over the fracture site was noted. After thorough debridement, removal of the nail and appropriate intravenous antibiotics, the infection was controlled. There were no signs of chronic osteomyelitis at the last follow-up. Two patients had broken distal locking screws before fracture healing (Fig. 2). Secondary surgery was carried out for broken screws and dynamisation. Totally, the early complication rate of the ULN group (9.5%) showed no significant difference compared with the ILN group (10%) (P=1.0).

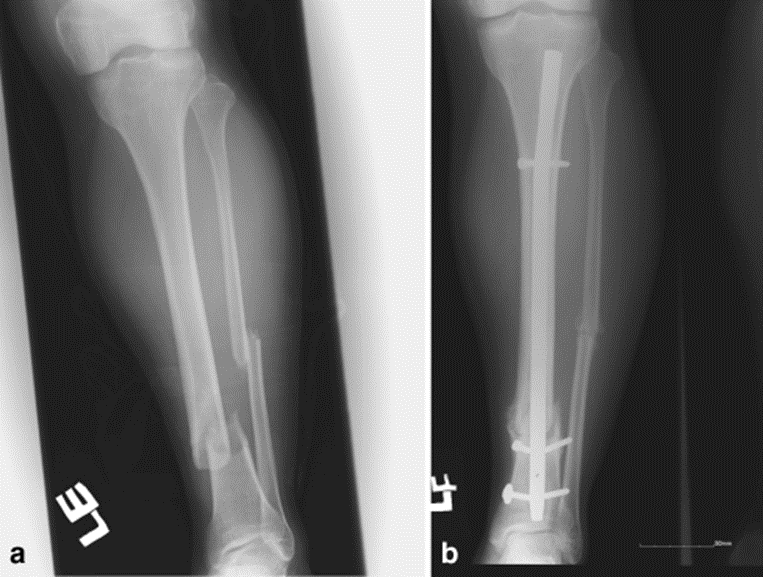

A 38-year-old male patient with left distal-third tibial fracture was treated with interlocked nailing. a Preoperative AP view showed a displaced tibial fracture. b Radiograph at postoperative 12 weeks showed broken locking screws

Twelve months postoperatively, all patients’ functional scores were evaluated. The mean score of the ILN group (33.2 points) was similar to the ILN group (34.1 points) (P = 0.48). In the ULN group, 19 patients (45.2%) returned to their previous work in 6 months. One year after surgery, 30 patients (71.4%) could do the same athletic activities. In the ILN group, 28 patients (70%) returned to their previous work within 6 months. One year after surgery, 33 patients (82.5%) could do the same athletic activities. There was no difference in returning to athletic activity between the ULN and the ILN group (P = 0.3). However, the ILN group had greater ability to return to their work 6 months after surgery (P = 0.03)